From Catastrophe to Concert

The story of a première

I have never liked calling myself a composer. Other people have done, but to me somehow it seems far too presumptuous. In the same way I don't feel particularly comfortable writing about a project that is based largely around my composing. Wherever possible I prefer to quote other people, as I do in this article.

This is the story of how a natural disaster in Asia led to a concert in a rural town in the southwest of England featuring musicians from three continents and the première of two of my works: the song cycle Idylls and A Himalaya Concerto.

The Catastrophe

On 25th April 2015 an earthquake of magnitude 7.8 struck the region of Nepal to the northwest of Kathmandu. It killed nearly 9,000 people and injured nearly 22,000. Two aftershocks on 12th May were of magnitudes 7.3 and 6.3, occurring to the east of Kathmandu. At least a further 153 people were killed and 3,200 people injured.

The Initiative

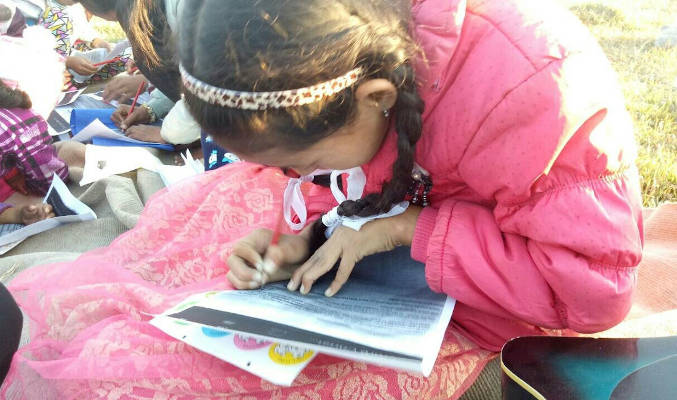

I am a trustee of a small UK-based charity called People Against Poverty. We have a couple of projects in Nepal, of which one was severely disrupted by the catastrophe. A few weeks after the earthquakes, in June 2015, our charity's Chief Executive Officer, Val Huxley, asked me if I would write a song to help raise awareness of the difficulties people in Nepal were facing and of the work that People Against Poverty was doing and continues to do in Nepal.

The very next day the clarinettist Idris Harries (Australia) asked if I would write a new clarinet concerto for him. I suggested using the concerto to achieve Val Huxley's objective and so was born the idea of A Himalaya Concerto. The only question at the back of my mind was: could I do it?

The Concept

I felt surprisingly relaxed about the project, never before having composed a full-scale concerto. I have been fascinated by mountains since my university days and so I decided to base the concerto on the relationships between mountains and the people who live with them. For each of the three movements I chose a mountain whose name and significance seemed to embody what I wanted to say with the music.

Ama Dablam means Mother's Necklace - the long ridges on each side like the arms of a mother (ama) protecting her child and the hanging glacier thought of as the dablam, the traditional double-pendant containing pictures of the gods, worn by Sherpa women. Despite its modest elevation (22,349 ft) it is a formidably dangerous peak to climb.

Dhaulagiri (Beautiful White Mountain), 7th highest mountain in the world, towers above the village of Shikha in the Annapurna Conservation Area in Nepal. Its summit (26,795 ft) is an astounding 18,525 ft higher than the floor of the adjacent Kali Gandaki Gorge. Dhaulagiri is considered to be a real climbers' mountain. As the writer Emily Barroso said on hearing the music that I wrote, it embodies "the way that great mountains seduce, invite adventure and bring the spirit out to play – yet sometimes terrify."

The earthquakes had left many people dead and many more injured or otherwise affected. I wanted the last movement of my concerto to pay homage to those people and celebrate the resilience and spirit of communities as they overcame their problems. Communities needed protecting and transforming. People Against Poverty runs a child sponsorship scheme in Pokhara. To the north of Pokhara lies a mountain that is held sacred, being closed to climbers. It is regarded by the local population as the abode of Shiva, who in Shaivism tradition is the Supreme being who creates, protects and transforms the universe. I chose that mountain to symbolise the last movement of the concerto: Machapuchare (Fish Tail).

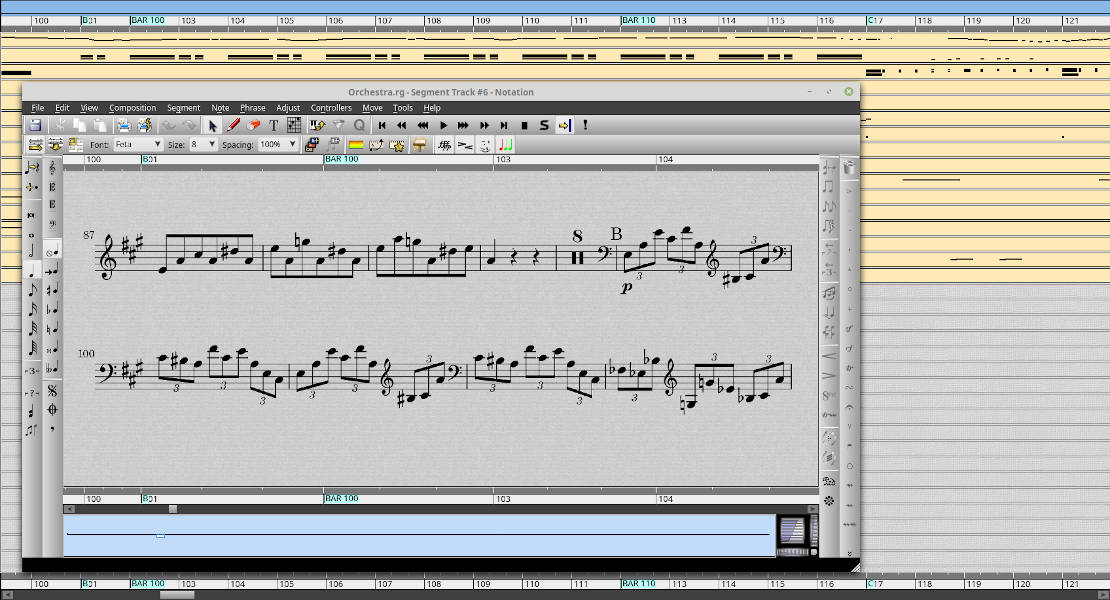

Composing

I decided to use the clarinet in A rather than the more common B-flat instrument, because of its somewhat warmer tone in the lower register. To that I added a secondary solo part for a concert grand cimbalom, with which I had fallen in love through many years of working in Romania. The charity was working in Romania also, so the combination of Himalayan theme and cimbalom seemed appropriate. The cimbalom is a fascinating instrument. The layout of its strings is quite bizarre and it is capable of a wide variation in tone in the hands of a virtuoso.

I completed the composition including typesetting the 133-page full score and all the orchestral parts in about five months, starting with the second movement, then the third and finishing with the first. As to whether the result was any good, I leave that to three people whose views I trust.

I love it. I enjoyed the moodiness and swirling mist of the first movement, dark and dramatic, very cinematic; the expression of emotions in the second movement, with that sliding clarinet; and the third movement, which for me is so joyful. The music is so fresh and takes you straight into the heart of the Himalayas. Beautiful clarinet writing and a major addition to the repertoire.

Fantastic work. The first movement carried reminiscences of Stravinsky and also of Prokofiev's piano concertos. The second movement was a nice extension of the previous material and had Mussorgsky-esque moments, particularly the interplay between clarinet and cimbalom. The final movement was brilliant. I adored the way it approached an almost shimmering Gamelan-type texture at times.

Well, congratulations! I listened to your composition and I must say that the clarinet part certainly is challenging. You have stretched the instrument to new paths. Very impressive work indeed!

The Sales Pitch

We then had to find an orchestra willing to play it. Idris Harries and Jordan Black (woodwind finalist, BBC Young Musician of the Year 2012) were both willing to take on the clarinet solo. Two professional cimbalom players (Andre Bonetti in Brisbane and Robert Millett in London) also expressed interest. The director of the Bath Philharmonia, Jason Thornton, described the concerto as “a work of considerable merit” but expressed reservations about taking on a work by an unknown composer unless we were willing to cover the production cost. At around £100,000 that would have needed serious sponsorship. I approached also the director of the Enescu Festival Orchestra in Bucharest. He loved the idea of a new concerto featuring the cimbalom but admitted that the orchestra was seriously short of funds. We needed a lot of money or a 'Plan B'.

Finally, in exasperation, Idris Harries said to me one day in 2018, “I've had enough of this. You mentioned doing the orchestra on your keyboard. Let's do it.” Plan B it was.

The Project

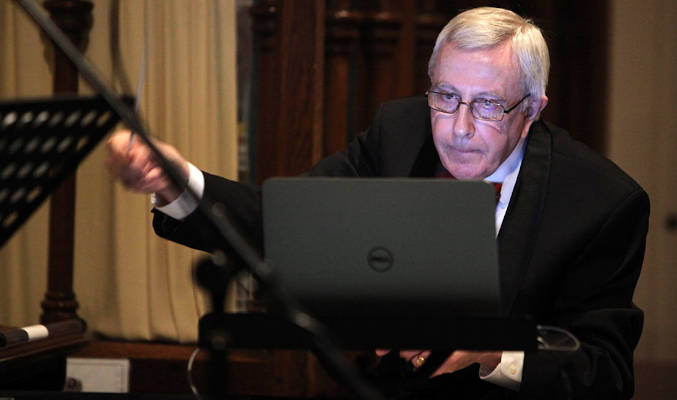

The plan, therefore, was that Idris would play the clarinet solo live, I would play the cimbalom solo live (albeit on an electronic keyboard) while conducting whenever possible, and a MIDI sequencer would 'play' all of the other instruments in the orchestra. (A MIDI sequencer is a piece of software that tells the keyboard which notes to play on which instruments, when and how. Think of it as an orchestra made up of androids.)

Playing a virtuosic concerto in this way, with a largely synthesised orchestra, is no easy task. In a live music situation, with a real orchestra and a conductor, everyone is listening to everyone else (or should be!) so that keeping in time with each other is a kind of corporate effort. By contrast, a MIDI sequencer doesn't listen to you. It just keeps going, regardless - and if you do something even as seemingly insignificant as hold a note slightly too long, things can fall apart very quickly. If live musicians get out of sync with a MIDI sequencer it's totally up to the musicians to put things right. So Plan B, simple though it might seem, would test Idris's and my musicianship to the limit. The fact that Idris and I lived on opposite sides of the world meant that we had to do everything over the internet and by video.

The Production Team

The first thing we needed to do, though, was to decide when and where the concert would take place. Logistically it made sense to go for Trowbridge in the west of England, for a number of reasons. Having made that decision, the only realistic date would be 12th January 2019. I became de facto project manager. Charlie Jackson-Allen, a professional musician based in Trowbridge, was keen to join the team. Val Huxley as CEO of People Against Poverty was also a key person. We rounded the team off with Stewart Palmén, who became our all-round 'logistics guy'. Media specialist Richard Fairhead contributed some useful suggestions, from his base in Cyprus.

Musicians and Programme

We invited the Chinese soprano Chen Wang and the Manchester-based pianist Jonathan Ellis to join us, making up a musical team of four. The first half of the programme would consist of Idylls (a song cycle that I had written for Chen in 2015) and A Himalaya Concerto. The second half consisted (eventually) of music by Liszt, Puccini and Mozart.

The Concert

All profits would be donated to People Against Poverty. Charlie Jackson-Allen, Stewart Palmén and I agreed to indemnify the charity against any losses. Two companies sponsored the event: the Trowbridge-based international development consulting company Landell Mills and my own company, SB VisionConsult. The Stallards Inn in Trowbridge agreed to provide refreshments.

Interviewed in Queensland about A Himalaya Concerto by journalist Claudia Alp before flying to the UK, Idris Harries said that "while the piece was in standard concerto format, there was nothing standard about it."

The concert was announced on every social media and publicity platform that we could reasonably access without spending ridiculous amounts of money.

We billed the concert as a ‘once-in-a-lifetime experience’ and a ‘musical extravaganza’ because concerts at which a local composer is present to have two of his works premièred by top-flight international musicians just don’t happen in Trowbridge.

Well, they do now – and those people who came loved it.

I had tears in my eyes. Never did I think I would hear such music in Trowbridge. Just … wow.

It was a cracking concert. For me the highlight was A Himalaya Concerto. I was captivated by the tone of instrument and player the moment Idris started tuning! I immediately knew we were in for a treat. Full marks to Stuart for even knowing that a clarinet was capable of some of those sounds, and full marks to Idris for such controlled, beautiful and seemingly effortless playing.

That concerto … it just is Nepal. I’ve never been there or heard Nepalese music, but the concerto transported me there instantly.

If you've ever wondered how a composer feels the first time he or she hears a composition performed by professional musicians, well, I can't answer for everyone - but I can tell you how I felt.

Our concert opened with my song cycle Idylls. The very first notes that our concert audience heard were the thunderous, bell-like chords on the piano that open Ring out, wild bells. I had not discussed with Jon Ellis how I wanted them played and yet immediately his interpretation felt right. He opened Saint Agnes' Eve more slowly than I had envisaged it, but as an interpretation it worked very well. Chen Wang gave a beautifully poignant performance, particularly of Saint Agnes' Eve. How did it feel for me? Spellbinding and humbling to a degree. Somehow I've never quite come to terms with the fact that I can compose!

I considered it a minor miracle that Idris, I and the MIDI sequencer got to the end of A Himalaya Concerto at precisely the same time! My immediate reaction was an overwhelming sense of YES!! we did it!

I knew that I had pushed the boundaries when I wrote the concerto, especially in the second movement where I had done just about everything that orchestration textbooks tell you not to do when writing for the clarinet. The unearthly swooping glissandi that I demanded of the soloist were the defining feature of the work and Idris carried them off with aplomb. The performance was the culmination of a close collaborative effort, in which I suspect Idris and I had learned from each other how to extend the musical language of the clarinet.

The Achievement

Each person arriving was given a folio of information about People Against Poverty. Throughout the concert people were reminded of the aim of the event. An autographed full score of ‘A Himalaya Concerto’ finally fetched £60 when auctioned during the interval. What did we achieve? We made a modest profit for People Against Poverty, but the much greater achievement was the kudos in arranging a fully professional and top quality concert, in a way that drew people in and helped to sell both the Charity’s mission and the concert venue and concept. In short, we established a concert brand of sorts. As Val Huxley said to the audience, "If there had not been a catastrophe in Nepal, Stuart wouldn't have written his concerto and you wouldn't be here tonight."

The Conclusion

We promised a once-in-a-lifetime experience: and to judge from audience reaction on the night, we delivered what it said on the can.

My sincere thanks to the following people, without whom this entire project would not have been possible:

- Kira-Lily Thorne, for being an exemplary flower-girl

- Chen Wang, for having the voice of an angel, for being a lovely friend and for Paddington

- Val Huxley, without whom my concerto might have been just another clarinet concerto

- Idris Harries, for having faith in me as a composer and the courage to play the result

- Greg Knowles, for advice on writing the cimbalom part of A Himalaya Concerto

- Andre Bonetti, for checking the cimbalom part of A Himalaya Concerto

- Jonathan Ellis, pianist extraordinaire, for his brilliant and definitive interpretation of Idylls

- Charlie Jackson-Allen, for introducing me to Jonathan, his amazing enthusiasm and being our Master of Ceremonies

- Stewart Palmén, for all the planning and logistics that helped to make a success of the concert

- Celia Lansley, for a splendidly atmospheric set of photographs of the concert

- Rob Jones, for helping to clear up all the gear after the concert

- Richard Fairhead, for his wealth of experience and for keeping me on an even keel

- The Stallards Inn, for keeping us all topped up with beer, cider and other such essentials of life

- Landell Mills and SB VisionConsult, for sponsoring the concert

- My wife Esther, for putting up with so much noise all the time